I’ve written several love letters in the past, published here, that bridge the gap between gaming and gnosis. I’ve also written about the many esoteric notes that the documentary series, Hellier, hits during their investigation but misses, due to the crew just not being aware of this detail or that. But now I bring to you a breakdown of what might be my personal grand unification theory. All my favorite shit rolled into one ambitious study: Gaming, Hellier, the occult, and H.P. Lovecraft.

Because I can’t just can’t be concise about this stuff and Substack eventually drops a gavel and tells me to cut the shit and get to the point, I’m going to break this up into several parts.

Part 1: Delta Green

Part 2: The Whisperer In Darkness

Part 3: Crowley, Lovecraft, and Grant

Part 4: Putting It All Together

Important note: I am in no way associated with the Hellier production, Planet Weird, etc. I’m just a fan with a substack and too much time on their hands. These articles are in no way endorsed by the Newkirks.

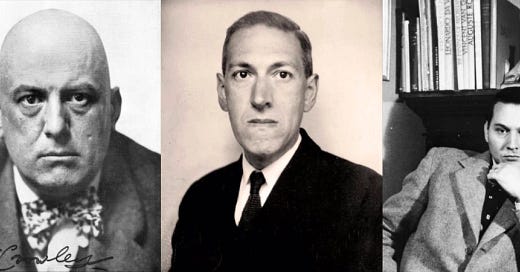

Part 3: Crowley, Lovecraft, and Grant

Back when I first started taking occult practice seriously and actually, you know, practicing, I sought out everything I could that would shore up confidence in my weird belief system, a syncretic pastiche of everything that bridged the gap between supramundane consciousness and UFOs. That stuff is out there but it means digging through the trash to find it. Discovery’s Ancient Aliens did me no favors and the Sedona crowd made sure that a good deal of Google searches about UFOs and the occult were heavily laden with references to dolphins, Christ consciousness, and dorky stories about ET contact that barely concealed the thick vein of fascism that would eventually take the spotlight in the Qanon scene, causing one group of psycho maniacs to accuse the other group of psycho maniacs of being psycho maniacs. But I wasn’t shit out of luck. I did find results. A DKMU-adjacent group of chaos magicians named Operation Intruder were actively trying to stage UFO abductions of world leaders, which I found hilarious and am firmly in favor of. I found Allen Greenfield’s Secret Cipher of the UFOnauts, a book which I found fascinating but initially dismissed because I had no context to understand it by. I hadn’t read The Book of the Law yet and hidden ciphers in occult texts wasn’t something that was on my radar. I was, at this time, a novitiate chaos magician with not much experience under me but for Arch-Traitor Bluefluke’s comic book guide to chaos magic.

But then I found Kenneth Grant.

You’ll read Grant but not Greenfield? I hear you ask.

Bear with me.

The Grant title that initially grabbed and held my attention was Outer Gateways. It has a wild cover that’s hard to ignore and a stream of consciousness narrative that is equally hard to follow. In Thelemic thought, I’m actually a bigger fan of Grant than I am of Crowley. Aleister Crowley, for all the coverage I give him here and the noted defenses I’ve made of his philosophy, was a gigantic piece of human garbage. I try to be careful to make this point whenever I write about him and I wonder if on his deathbed he looked back on his life and realized by how much he’d missed the mark but the core of his writing stands: Crowley, for whatever reason, was delivered a powerful message about the potential for mankind to realize its place in the cosmos. Aiwass, however, was woefully misinformed about the sort of person he delivered that message to and all the narcissistic baggage the dude would attach to that revelation, confusing his own obsession with himself with divine inspiration, undermines the gnosis of Thelema.

And Kenneth Grant helps matters none in his fawning love letters to Crowley scattered among his prolific body of published work. But Grant does something that Crowley could never be bothered to do. He realizes that a pan-global divine truth can’t begin and end with the Levant and India. Crowley clung to these revelations because at the time of his reception of the Book of the Law, Europe was balls deep in the throes of Egypt-mania. Archeologists were digging up tombs and treasures left and right and there was no shortage of Alexandrian manuscripts turning up. England also had significant colonial interests in India but sub-Saharan Africa and African diaspora religions also shared commonalities with Crowley’s darker riffs on spirit if you looked at them in a certain light, as well. And there’s something to be said about the spirituality of the landscape that all mankind sprang from. Grant was not the first mystic to seize on this idea but he’s one of the first to give broader exposure to Michael Bertiaux, author of the notoriously opaque Voudon Gnostic Workbook, who made a lot of these important connections.

But if I’m being honest, the reason I cracked Outer Gateways is because I’d read that Grant wrote about things like Yog-Sothoth and the Necronomicon as if they were real.

What if Lovecraft’s monsters were real is a fairly ubiquitous trope in horror media these days. Peter Levenda has some novels on that topic and Charles Stross has a fun series of spy novels along these lines, as well. But Grant spices up your occult life by very seriously approaching the fiction of Lovecraft as though it’s non-fiction and as crazy as that may sound, there’s something to it.

Grant’s Typhonian current is tough to put concisely but in short, it’s preoccupied with the darker side of mysticism. If you’re reading this, then you’re probably at least familiar with Kabbalah but may not be familiar with its flip-side, the Qliphoth. If the Sephiroth are emanations of God’s creation, then the Qliphoth are what’s left when creation is done or aborted. They’re the byproducts and empty shells and there be dragons. Most Rabbis and mystics address the Qliphoth as if you’re flipping over a record, or to be more contemporary, The Upside Down from Stranger Things or The Black Lodge from Twin Peaks.

Grant referred to the paths of the Qliphotic tree as The Tunnels of Set, Set being the Egyptian version of Satan (kind of), but he also referred to these paths as a cosmic place that a willing magician could project their consciousness to and eventually landed on the name The Mauve Zone. The Mauve Zone and The Tunnels of Set are not the same thing, though. The Mauve Zone is a sort of intermediary space between here and The Tunnels and it’s in this place that intelligences from out there can interact with intelligences from in here and the intelligences from there are horrific aliens, aged beyond time.

And this is where Lovecraft Country comes into play. It’ll come as no surprise that Grant was a fan of pulp science fiction and fantasy and was familiar with Lovecraft’s fiction but he was also extremely familiar with Crowley’s business and noticed some very strange coincidences and began to formulate an opinion that Lovecraft and Crowley were both writing about the same thing but using different language. To Grant, it was as if Aiwass was also speaking to Lovecraft as he delivered revelations to Crowley and I have to admit, the parallels are fucking nuts!

In The Call of Cthulhu, Lovecraft sets the discovery of a raving orgy of maniacs worshipping Cthulhu in the New Orleans swampland in 1907. At the same time, Crowley, a raving maniac and orgy-enthusiast of note, was writing Liber Liberi vel Lapidus Lazuli in which he channels the word Tutulu and claimed not to know what the word means or where it came from and yet, there it is. Now, Call of Cthulhu was written in 1926 but to the best of anyone’s knowledge, neither Howard nor Aleister were aware of each other’s work. Liber Liberi vel Lapidus goes on, referencing a “sorry statue” carved of black stone and a being lying forever in a mighty sepulchre, which sounds an awful lot like The Horror in Clay and the sunken city in which Cthulhu resides, R’lyeh.

In a similar Class A document, Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente, Crowley writes about The Abyss of the Great Deep, The Slayer in the Deep (which sounds like a Lovecraft title, if I’ve ever seen one), and God’s messenger (who stands on the threshold - more Lovecraftian title style), with eyes like poisonous wells, an old and gnarled fish with tentacles whose appearance when the stars are right causes the air to stink, much as R’lyeh does when it finally rises in the climax of The Call of Cthulhu.

It should be noted that one of the lesser-known qualities of Cthulhu is that it’s not a God on the level of the supreme deities of Azathoth (whom Crowley also makes reference to in Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente as the Death-Star). Cthulhu is a priest of the Outer Gods and a servant of that Death Star that came to Earth in the times before mankind.

It doesn’t end there, either, but I only have so much space to write in before I have to stop. Grant, through his vast body of work, manages to form a pretty convincing argument that Lovecraft and Crowley were often talking about the same thing. Crowley never fully grasped their significance, being that he didn’t have the other half of the puzzle pieces that Grant ultimately found and Lovecraft, being a cold man of science simply couldn’t regard his visions as anything more than horrible flights of fantasy. Yog-Sothoth, described by Lovecraft to be a pulsing mass of globes could reasonably be compared to The Tree of Life and being that Yog-Sothoth is a sort of gatekeeper or opener-of-the-way on the way to Azathoth, you could be convinced in a way to accept the comparison since the Tree is a sort of door between us and God. But are we talking about capital-G God here or The Demiurge as God? In the latter sense, the Demiurge is understood to be a horrific abortion of creature, spawned by the Aeon Sophia by means of parthenogenesis and then cast out and trapped beyond, blinded and stuck in a universe of its own creation, tormenting the beings that it cursed into existence. In many ways, Lovecraft’s Azathoth is this very being. It’s a blind idiot god that lies at the center of all things. An orbiting orchestra of servitors flute away at some sort of reedy music meant to keep Azathoth asleep and as long as it sleeps, we’re safe because all it can do is dream shit into existence. It’s trapped in its own dream and has to remain asleep because what happens to the dream when the dreamer wakes? Is he not describing The Demiurge?

To round things out, I bring up Peter Levenda once again, whose book, The Dark Lord, was instrumental in helping me sort this all out and make sense of it all. In this book he points out that where Crowley channeled most of this business in the ways that a spiritual medium might, at the same time that was happening, Lovecraft was receiving all of his ideas for horrific monstrosities from beyond space and time in his own extremely vivid nightmares. The dream world being the place where many magicians are known to receive messages and visions, it just has to be noted that the eponymous call from The Call of Cthulhu was a hypnotic obsession sent to people while they dreamt. And I absolutely have to mention here the entire Mythos-adjacent Lovecraft series known as the Dream Cycle, which is a mystical fantasy land that sounds too similar to Grant’s Mauve Zone to simply let slide. In these Dreamlands, Lovecraft’s recurring character, Randolph Carter, a roman a clef for Lovecraft, himself, can transport his consciousness to and from the Dreamlands at will. Crowley would have simply called this astral projection but Lovecraft, through his surrogate Carter, seems to be implying that he had a degree of control over his own dream states.

Back to Levenda. Not only did Levenda help me with this, he also helped Grant sort out his own cosmology and ritual practice by way of The Necronomicon, published by Avon Books sometime back in the 1970’s. The book, which just about every dorky edgelord bought on sight and displayed proudly next to their Dungeonmaster’s Guide (such as I did) is credited to the original Lovecraftian author, The Mad Arab Abdul al-Hazred with an introduction by the singularly named Simon. Simon, it turned out, was Peter Levenda. But novelty or not, Grant saw this book as a workable grimoire that, because of the connections he drew from all of his combined sources, allowed conscious entry to the Mauve Zone where you could have audience with Nyarlathotep if one so desired to sacrifice their sanity to gnosis.

So we’re rounding the bend for the final lap here and in the next and final part, I’ll roll it up and put it together in a way that ties H.P. Lovecraft to the Hellier phenomenon. But before I leave you to ponder this edition, I treat you to this final Lovecraftian tidbit.

Written in 1904 at the age of 14, H.P. Lovecraft penned his first horror short story, a piece called The Beast In The Cave. It concerns the trials of a man who, while exploring the Mammoth Cave system, becomes separated from his guide and is lost in the caves. As he tries to find his way back, he encounters something in the darkness of the cave and through shit luck manages to hurt it enough to kill it and when he finds it, it turns out to be some sort of human being, devolved into a sort of cave goblin.

The Mammoth Cave system is in Kentucky.